The Aymara new year is celebrated on the winter solstice every year in Bolivia. Indigenous and tourists alike travel to a number of popular destinations to celebrate the festival, two of the most popular being Salar de Uyuni and Tiwanaku. Indigenous Aymara President Evo Morales has declared the Aymara New Year a national holiday, a subject of debate yet a popular festival among Aymara native and non-natives alike. During the ritual, the people worship Pachamama (mother earth of the andes) and Inti (the father of the sun).

I was originally going to go to Salar de Uyuni on a bus for press with my friend Alexandra, as visiting the vast salt lakes would be the prime way to experience the Bolivian tradition. However, Tiwanaku was much closer, slightly less glacial, and my Spanish professor was going. She said that there would be plenty of dancing to distract from the cold, and live bands. This was about to be awesome. So we stacked on layers until we were nearly immobile and packed blankets and sleeping bags. With huge bodies and huge packs, we trudged up the street with limited peripheral vision and hailed the cab that we would be sitting in for the next hour.

We took the cab to the most dangerous part of La Paz, El Alto to meet with people that seemingly existed. El Alto is what a few of the girls called “real Bolivia,” which I prefer not to believe, as it is much more impoverished than many other parts. Tents fashioned from wood and tarp lined the road, and as the wind blew the makeshift doors open, we realized that these were homes, lit by a single lightbulb. Since I have complained much less about the draft in our Sopocachi house.

Our housekeeper, Virgenia, has a sister named Fabiola that was going with friends that owned their own minibus. This was more fortunate that we thought, because as three American girls in a non-tourist environment, we would have been hopeless.

It took ages to navigate to where we would meet Fabiola, as El Alto is an everlasting swap meet. [photo] We sat in the taxi watching bundled Cholitas with babies bouncing in the sacks on their backs, bartering and fingering goods from shoes to Cholita skirts.

We stopped at the corner where we were to meet her, and the street was swarming with locals. Bundled up and barely mobile, we kept our backs to the wall of a building to avoid being robbed in what is known as pick-pocket central. We barely remembered what she looked like, so we were shouting her name at random people who must have been wondering what we were doing there.

She finally found us, immediately telling us to watch our backs as we weaved through the masses of late-night consumers. We finally came upon a privately owned mini bus parked on a dark street.

We sat in the back of the bus and waited to begin the journey, still excited but slightly irked. While we were parked, multiple people poked their heads in, asking if we wanted to buy coffee. Cholitas clawed at the sides of the bus, trying to get home, not knowing that we were heading towards the middle of nowhere, far from their homes. The boys began filling the bus with strangers, not quite as bundled as us, whom Maricielo, who speaks fluent spanish, later told us that they were poking fun at us.

The traffic was horrendous, but we finally got moving. The farther out of the city we traveled, the deeper into the darkness we plunged, and the more unsure we became. We came upon bumpy road, rumbling on rocks and dirt. We all had to use the restroom, which to privileged tourists is like a death sentence, because no matter where we passed during the journey, it was either desert or holes in the ground.

We finally arrived in the dimly lit town of Tiwanaku, the van spreading the people like a red sea, causing them to peer into our windows, their breath visible.

Tiwanaku, like many areas of La Paz, looked like a night market more than anything. Women selling clothing, food and alcohol stood in front of the graffiti-covered walls and next to piles of rubble. Lovely restaurants and hostels drew a sharp contrast with dilapidated buildings and makeshift signs. We laughed uncomfortably as we saw the sign for the bathroom we would be using, propped in a dark alley, and stopped laughing completely when we entered.

We needed to sit somewhere warm, and we were hungry, so we slowly made our way through the thick towards one of the many “cafes.” This one was run by two Cholitas who made sandwiches out of bologna and hamburger buns, coffee and tea, backed by shelves full of coca cola. I discovered here that the Cholitas are much more approachable and conversational that they appear. One was telling me about the “jovenes borrachos (drunk kids)” who passed out in front of her cafe the previous year. Conversations like these are what drives me to learn to speak spanish fluently, as well as gain some ground on local dialects and slang. These women are quite charming.

It was freezing, and although windless, the temperature bit at us through our thin gloves, weaseled it’s way through our many layers. “Abrigado” and “prendas” were words I heard often through the bitter night, meaning “bundled up” and “layers”.

Turned out that there were no bands, no dancing, just a bunch of people using their vodka blankets to stay warm. Apparently some borrachos from the past year caught a tree on fire and caused damage while raging to a live band, and for this reason the fun had been revoked. But the people had other means of having fun. We walked through an alleyway where women made hot alcoholic drinks and people sat in the many tents laughing and drinking.

We came upon an open area with some dry brush, and the guys decided to start a fire for warmth. What would be highly illegal in the United States apparently is no matter for concern in this ancient town in Bolivia, and although police were crouching at every corner, they had other concerns (about what, it beats me). The fire was more smoke than anything, tainting our clothing and convincing us that it was time to attempt to sleep.

Once again I would like to express gratitude towards Fabiola and her friends, as we would have had to sleep outside-or not at all- if we didn’t tag along with them.

Nevertheless, we couldn’t sleep; still wearing all of our layers and wrapped forebodingly in blankets and sleeping bags. People were shouting outside, and when I heard drums around 3:30 am, I knew we needed to make the most out of this situation that we had unknowingly plunged ourselves into.

I woke up Catey, who said her leg was basically frozen, and we left the bus to keep our legs busy. Thank goodness we did, because the next couple hours were the snippets of experiences that made Tiwanaku worthwhile- or at least memorable.

We sat in a “cafe” and asked for tea; the woman promptly sat us down and proceeded to ladle a hot amber liquid into a reused alcohol bottle, handing it to me with plastic cups. It smelled of rum. In my terrible spanish I told her that “No quiero alcohol, solamente te..” to which she replied that it wasn’t alcoholic, but rather good for the cold. Potata-Potato, right?

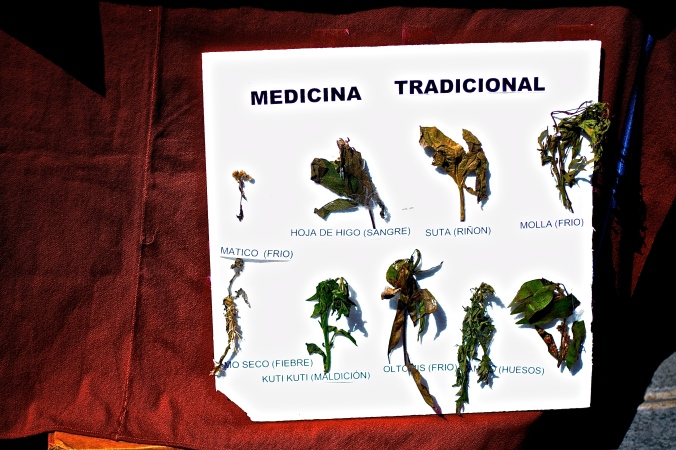

We drank a few cups and left, for the first time not wanting to turn this experience into more of a party. We went to the neighboring cafe and asked a couple locals if we could share a table with them, beginning a great conversation, despite the slight language barrier. We ordered coffees and egg sandwiches which, at the moment, were the best thing we had ever eaten. The men, drunk, were great fun to talk to and very tolerant of our spanish. They told us about the tradition of tribute to Pachamama, through which the Aymara people will always pour a bit of their food or drink onto the earth before enjoying it themselves. He said that even the poorest people will do so, more so than the wealthy with their pricey libations.

We parted ways and were drawn to a fire like mosquitos, where a group of borrachos fell in love with us immediately. Whilst a swaying Bolivian was whispering sweet nothings into Catey’s ear, I spoke with a guy with a braid, his left cheek bulging with chewed coca leaves. He asked questions about traditions like these in the United States. After telling him that we’re journalists with the Bolivian express, he begged me to show the beauty of the tradition, not the borrachera. I assured him that we were simply there to learn about the tradition, and we’rent reporting on it, because in reality, the traditional culture was not as apparent this year.

At this point, light was beginning to appear along the horizon so we returned to the minibus to retrieve the others, who of course had been worried about us. We grabbed our cameras and followed the masses in their pilgrimage towards the Ritual of receiving the sun. The light revealed people laughing and stumbling, seated confusedly against walls. People were passed out in distant fields, and some were stumbling towards the sun, yet not getting anywhere. The colors of traditional dress were brightened by the lightened sky and Cholita women were still murmuring their sales pitches to passersby.

A makeshift nightclub housed in a roofless building was bumping with the beats of a DJ and drunk people rambled on stage, dancing to the tunes. The people that still had their wits danced an indigenous dance around broken bottles and the remnants of fires. It is now one of my objectives to learn this dance.

When we reached the gate through which people passed to attend the ritual, we were informed that locals costed 10 Bolivianos to enter, while tourists costed 80B. We turned around and walked as close to the fence as possible, which sufficed perfectly. Locals stood with their hands to the sun as it rose over the curve of the earthen plains. This was the beginning of the new year, and the Aymara people welcomed it by grasping at the sun that dawned upon the year of 2013.

At the same time, I realized why the people stay all night to await the fleeting moments of sunrise. By enduring the freezing nights, the people were able to truly appreciate the redeeming warmth of the sun as it blanketed their stiff, open hands.

The Aymara flag (or the flag of the plurinational state of Bolivia) was raised beyond the chainlink fence where the ritual occurred, and the Aymara and Spanish-spoken ritual echoed over the field.

We walked and relished the warmth of the sun after leaving the ritual. We sat in the van, and although delayed with a dead battery, we were just happy to be warm.

Coming soon: Hats that read “I froze my ass of and survived the Aymara New Year 2013, Tiwanaku”