ABSTRACT

The proposed research project was an ethnographic study of food culture in México. Specifically the project explored how notions of health and well being articulated with practices and ideals of food consumption. This study was conducted among residents of a rural community in Yucatán that is economically dependent upon mass international tourism. This research was investigated through two questions:

- How do people experience food in relationship to health and how is food perceived as creating health?

- What is the disjunction and dissonance between how people talk about healthiness in terms of food?

The project consisted of semi structured informal interviews, participant observation and informal interviewing that was used to illicit and document information the way people talk about health in relationship to food. Semi-structured informal interviews were conducted to learn about simple rules governing meal structure and food choices. Informal interviews will be used to speak with both community members and those who prepare food to understand preferences and perceptions of food and health. The use of participant observation of food preparation and consumption provided information about what is said about food and health and what is practiced. Analysis of the data obtained from each of these methods allowed for an understanding of the notions of well being among the people in Pisté, México.

Overall, the study aimed to contribute to the existing literature about the cultural significance of food and how people’s perceptions relate to physical and mental health.

INTRODUCTION

This study aims to analyze the development and continuance of food culture in Yucatán, México through the lens of perspectives of health and consumption habits.

I was originally drawn to the rural town of Pisté in Yucatán, México by a falsely advertised lore of a “traditional medicine” that I was almost immediately told does not exist. Although I did learn about tidbits of ancestral medicine— such as using crocodile’s penis to cure impotency and venturing into the monte, or forest, to find fruits that will cure cancer even after its onset— these are no longer prevalent nor recognized, and according to my informants, the majority of people in the town would not travel at two a.m. to see a fearful bruja to cure their ailments. Furthermore, According to my host family, the only person representative of Redfield and Villa Rojas’ H-men (Redfield and Villa Rojas 1934) was a charlatan living on the other side of town, which they insisted the locals do not trust.

Nevertheless interested in notions of well being, I began to recognize the pride at the axis of the self-perpetuating cycle of food consumption habits in Yucatán. Therefore, the project morphed into an analysis of traditional elements of Yucatecan food, how those traditional elements have been preserved and used, and the social significance of food and how the people in Pisté perceive and react to the impacts of their diet.

The project is conducted in the month of July over a time period of four weeks in the context of the small rural town of neighboring Chichén Itzá, which accommodates a consistent influx of tourists interested in Maya heritage. A great number of local people have preserved Maya folklore and for many reasons continue to utilize traditional staple foods and thus, the information that my informants willingly shared has served as the basis for this report.

I will begin by outlining the methodology that I applied to conduct fieldwork, including a brief discussion of my informants. I will then introduce the area of study in terms specific to food consumption, followed by a profile of my homestay family, who served as primary informants. The key data of this report is to be discussed in terms of traditional diet, perceptions of health, and the social significance of food. Prior to my conclusion and self-evaluation, I will provide a brief analysis of the data that I collected during the four-week study.

The cornerstone of this report is the analysis of how traditional elements of food and diet have been preserved and perceived by the people in Pisté. For this reason, it is necessary to define the word, which is often misused. The term is frequently used to express something more or less historical that has been preserved, which although is useful is incorrect. My use of the term “traditional” in this report will refer to the etymological definition: as a “statement, belief of practice handed down from generation to generation,” as well as the way multiple sources define the word, as in reference to something native to a region and acknowledged by a population; for example, Yucatecan food is simply the food eaten in the region. Thus, any foods or dishes that are not rooted in the primary Yucatecan staples, which will be discussed shortly, will be referred to as “non-regional.”

METHODOLOGY

To obtain information about what people eat, why, and how it makes them feel, I decided that a number of informal interactions and observations would draw the most useful information. My research methodologies therefore included a number of informal interviews and casual conversations with food vendors, local people and multiple age groups so that I could understand what foods are most commonly consumed and why. Semi-structured informal interviews were employed to engage with multiple groups to discuss their perceptions of health and outlook on diet; these groups included families, kitchen employees, taxi drivers and health club members. Finally, I used participant observation by working in a local restaurant, La Gran Chaya [1], with the goal of learning about different traditional dishes, as well as gaining an understanding of attitudes towards kitchen conduct and food.

Due to the fact that the majority of people in Pisté enjoyed discussing and sharing food, I found that I did not need to employ many tactics to uncover information. However, I strategically formed bonds with food vendors so that they would be happy to share time and information with me, and I made sure to greet the majority of people sitting outside of their homes so that I could potentially be invited inside to observe food preparation or consumption. In the kitchen at La Gran Chaya I made sure to help with simple tasks so that I could simultaneously observe kitchen customs and interactions. I also learned to prepare multiple dishes myself so that I could gauge the openness of the sharing of traditional knowledge and pinpoint the importance of certain ingredients used in a variety of dishes. Depending on the informant, I either tactically withheld or shared information about my vegetarian diet so that I would be able to glean supplemental information or specific types of responses.

With many of my research subjects I became friendly acquaintances; I made sure to form bonds and build bridges so that I could spend time with them more than once. However, a great percentage of my subjects were from my own homestay family, with whom I spent a significant amount of time so that I could observe their consumption habits and perceptions of food and health. Additional informants were simply acquaintances with whom I established rapport, or locals with whom I spoke in passing.

CONTEXT

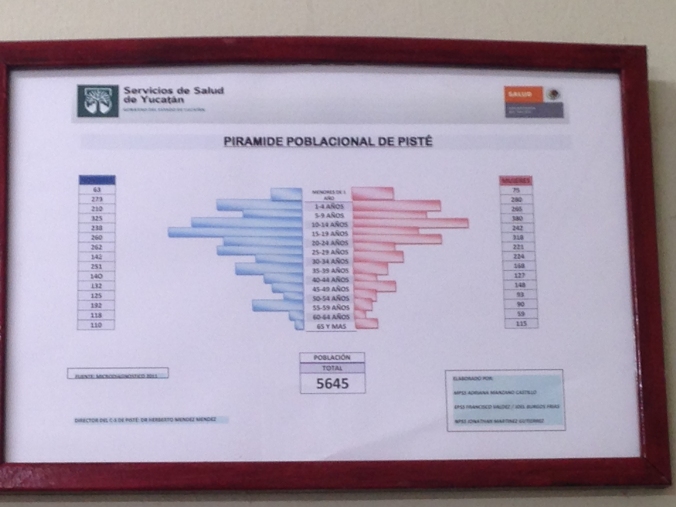

Pisté has a population just under 6 thousand (2011) with much of the demographic being young people between the ages of 14 and 20. The town was founded around the end of the 1940s by a group of Maya that wished to live within close distance from Chichén Itzá.

Both locals and those who pass through consider Pisté a town with a very relaxed lifestyle. The town has a center surrounded by most of the chain stores that the townspeople would need to use: Donuzusa, Super Willy’s, and multiple abarrotes. Food is available in many forms, and at many levels from commercially to privately owned shops. Depending on the season, on local trees grow sour oranges (chinas), limes, avocadoes, huayas, coconuts, chaya and crab apples (nance), and some grow their own chile peppers and herbs. A select amount of people—my informant guessed 25-30%— tend their own milpas[3] and grow corn, beans and calabaza squash[4]. For those who need most dry goods and other processed foods, they visit one of the chain stores or abarrotes, where snack foods and quick necessities like beverages, breads, meats or cheeses are sold. There are a few independently owned fruterias scattered between the stores, that sell fruits, vegetables, spices and sometimes candy. These stores are open throughout the day. carnicerias and panaderias often open on their own schedule, while these any many other convenient stores are closed during the lunch hour, between one and 5 p.m. Privately owned carnicerias sell meat based on the day of the week, which I will explain later on in this paper. There are a number of privately owned loncherias or even small convenient stores that open on their own schedule, and from these a friend or the well-versed local can often get discounted necessities such as Coca Cola, eggs, and snacks such as chicharrones. It is in a home with one of these shops, that I lived for my four-week stay, and I was able to do a great amount of my fieldwork by observing and asking questions at home.

The patriarchs of my large homestay family[5] are Doña Victoria Marrufo-Nah and Don Viviano Uh-Tun. Victoria, 52, stays home and tends to the household and to chickens that she slaughters and prepares for sale to community members[6]. Viviano, 55, is a jack-of-all-trades, but specializes in music; he plays guitar nightly at one of the nearby hotels as the head of his 3-piece band. He also works during the day at Chichén Itzá, selling refreshments and novelties to tourists. Victoria and Viviano have five children: Indalecia, 36, Jaime, 35, Edgar, 28, Joel, 23, and Josué, 15. Indalecia lives with her husband Javier, and her son Gibran, 17. Indalecia and her family spend the majority of their time at Victoria and Viviano’s house, where she works in a store on the other side of the home and sells American clothes that she purchases in bulk packets from Mérida. Indalecia also helps prepare food, and during the course of my stay, began selling tacos and sandwiches in the mornings out front of the house. Gibran will be attending nursing school in Valladolid by the end of August, and Javier works bi-monthly in Mérida, selling artisan goods. Jaime is married to Leydi, 25, and they have a son Ronaldo, 5. Jaime and Leydi live outside of town in San Felipe, but like Indalecia and her family, spend most days in Victoria and Viviano’s home. Leydi helps out in the household and cares for Ronaldo, while Jaime plays in the band with Viviano as well as uses one of the family’s pick-up trucks to pick up vendors from Chichén for 20—40 pesos a trip. Although the older children live separately, their income contributes almost directly to Victoria and Viviano’s household. Edgar works at Chichén Itzá selling artisan goods such as jewelry, purses, hammocks, painted clay figurines and masks. Also a contributor to the family’s household is Lissett, 14, a niece of Victoria’s who sells shaved ice and other beverages out front of the home in the morning. The whole family also sells chicharrones, machacados, and other goods at the storefront next to their house. The home is thus a three-piece block with two hand-made palapas, one for a garage and one as the kitchen in the back of the center home, where the majority of the family gathers, sits and enjoys one another’s company. Victoria and Viviano live close to one another’s families; Viviano’s mother and siblings live a few houses down, and the home of Doña Luisa, Victoria’s mother, is quite close as well. Both Victoria and Viviano speak Maya, although often fused with Spanish, as they still communicate with their parents daily in Maya. Indalecia and Jaime are also able to communicate in Maya and Edgar understands the spoken language, but the younger children cannot speak nor understand fluently. Like much of the town, the Uh-Marrufo family is catholic, and goes to mass every Sunday. The whole town knows them as the “Vivoras”, which means snake, and they are proud of the title.

THE “TRADITIONAL” DIET

According to Maya lore, at the beginning of time, Yum Hunab Ku, the creator of the universe, “Corazon del cielo,” began to create man. First, he created men out of clay, but he was too soft and didn’t serve. Second, he created men from wood, but these men were too stiff and couldn’t move about. Third, he created men from corn. These men were yellow, red, black and white, and they still exist today.

Don Viviano[7] is a milpero and a teller of stories. His favorite to tell is the story of maize, a story that sets his black eyes ablaze with pride. Don Viviano said that 7 thousand years ago (5000 B.C.E.), the Mesoamerican man was a nomad who lived on a diet of fruits, roots and fish. During this time, man discovered corn, recognized it as a reproducing, sustainable plant, and began to domesticate it. Soon after the domestication of maize, man adopted a sedentary lifestyle around bodies of water and formed aldeas, or neighborhoods. Soon enough, corn became the sobreviviencia of man, the source of his well being.

Fig. 7: My host father, Don Viviano, poses for a photo shoot after teaching me about the milpa, a small farm where locals grow their corn, beans, squash and chiles.

Man developed a way to grow corn through slash and burn agriculture, and developed a system of farming based around the rainy season, or ha’hali in Maya. For the milpas to produce, man needs six months of rain, and for this he asks the Maya rain god, Chaac. On the 15th of May, Don Viviano said, in the fields all over the world, the farmers will begin to plant their seeds. After months of careful tending, when the harvest is ready around the month of October, the milpero begins to pay attention to the ripening of his other crops: white and black beans, and different types of calabaza squash, which has vines that weave between the corn stalks. However, corn was always the milpero’s pride and joy. Before bringing the harvest to his family, he picks the biggest elote of corn, dries it and grinds it into a masa. This masa, he said, cannot be smelled, tasted, or enjoyed in any way by the milpero and his wife; this masa is used to make an atole[8] for the gods as thanks for yet another harvest. At 3 a.m., man and his wife will rise, prepare the atole by stewing masa in water, and carry it to an open field in a hicora bowl so that the spirits can drink it.

Once the gods have received man’s gratification, the harvest is theirs to use. When it is still dark outside, man and his wife awaken, she prepares a breakfast of beans and tortilla, fills the milpero’s calabaza jug with atole, and man will depart on his 3 kilometer-long walk to the fields. Throughout the day the man will work on energy he receives from the corn in his diet, and when the sun falls, he returns home, having burned every calorie consumed. This, Don Viviano said, is the true food of the Maya. Patting his muscles, he says, “solo masa de maiz está en el cuerpo del hombre.”

Following the Spanish conquest, domesticated animals added new sources of protein to the diet (Baklanoff 2008:22). According to multiple informants from Don Viviano’s generation and older, including Doña Victoria’s mother Doña Luisa, during the early 20th century many households only consumed animal protein if they raised their own pigs and chickens, and the emergence of community stores and carnicerias did not occur until later, when the population in Pisté increased in the second half of the 20th century.

Throughout my aggregation of data, I referenced Baklanoff’s study of globalization in Yucatán. He writes from the year 2008, but it seems that either much has changed since his analysis, or his region of study differs in many significant ways from Pisté. Balankoff (2008) writes that most observers define Yucatán as a “’traditional society’… made up of a complex and often conflicting set of traditions … [with] a remarkably uniform folk culture…(2008:5)” of which one of the elements is a diet based on corn, beans squash and chili peppers. Today, Yucatecan food is ‘traditionally’ centered around five staples, four are those which have been present since before the Spanish conquest of the Americas: the corn, beans, calabaza squash and chile peppers, of which can be said to represent grain, legume, vegetable and flavor, the latter being an obligatory part of the majority of Yucatecan dishes.

Corn is present during the majority of meals in its tortilla form, and some use the corn they cultivate to make elotes, or corn on the cob, and atole, a beverage prepared from water and corn masa made from grinding corn kernels after they had boiled and dried in the sun. As Baklanoff said in his study:

“Handmade corn tortillas are an essential part of breakfast, lunch and dinner; they serve as bread, potatoes and even as spoons (2008:114—115).”

Beans come in multiple forms and are pairings for meat, eggs, rice and sometimes, vegetables. Calabaza squash has been replaced by meat in multiple dishes, but is still present as one of the most-used vegetables in select dishes as well as is made into sauces; often the seeds are ground and used to make pipian, a traditional meatless dish made with chaya, a nutritious leafy green that will unfortunately not be discussed in this report. Chile, of which there are 7 main chile peppers sold in the produce stores, is present in nearly every dish, whether the mild ones are used to flavor while cooking or the hot ones are used for nibbling while eating. While not all residents of Pisté said they eat chile, they know at least one person who would refuse to eat without chile on the table. The types of chile peppers sold in the fruterias in Pisté and their uses are as follows: chile de arbol is considered a “dry” chile, and is used in a great number of dishes and salsas. chile dulce is also employed in a great number of dishes, it is diced and primarily added for a specific flavor. chile Serrano is likewise used in salsas. Chiles Kat, Gordillo and Jalapeño are used for chile relleno, one of the most popular Yucatecan dishes; these chiles are not valued so much for their spiciness as their size and flavor, as the seeds are removed to reduce the bite and the peppers are filled with meats and cheeses. Chile Habanero is the hottest pepper sold in the stores, and generally sits next to the plate so that a person can nibble on it while they eat. When chile is not present, as I have observed, people are likely to nibble on radishes in between bites. Based on this observation, I’ve found that all meals need to be perfectly balanced: not in food group, but in flavor; salty egg dishes with beans are balanced by avocado and tomato, while tacos with salty and savory pork must always include sharp onion with lime.

Through observations in multiple kitchens I noticed that flavors are pounded, soaked, ground, boiled, fried and squeezed into many of the dishes and components of dishes. For example, salt and lime is squeezed into red onion, and salt is used as a spice during food preparation rather than an accent immediately before food is eaten. Each cook takes pride in their use of a custom recado, which is a mixture of spices including garlic and pimento. Food is classified by its content of flavor in many cases; comida seca, or “dry food,” includes foods that have less sauces and condimento, or seasonings, while comida mojada is often drenched in sauces. In addition, one of my informants, who owns a carniceria, said that many customers will request pork with less fat, but the majority prefer an abundance of flavorful fat on their cut.

The fifth staple is one that was not mentioned in Baklanoff’s study yet is by far the most consumed across the board: meats. Throughout my gathering of data I found that meat’s role as the unquestionably vital part of a diet fundamentally based on those four staples is indeed complex and conflicting in many ways, and over time this proved to be a fundamental part of my analysis.

Meat is so important to the Yucatecan diet that each day of the week has its own particular meat. Mondays are beans and pork, and Indalecia said on these days the carnicerias are always out of pork. Tuesdays are chicken, and families will eat anything from a caldo de pollo (chicken soup) to a mole with chicken. Wednesdays bring pork back to the table, possibly in the form of local favorite cochinita, a shredded pork that stews in a sauce for an extended period of time. Thursdays are chicken once again, and one would eat pollo asado seasoned with ahiote, a red spice likened to pimento. Fridays are fish, which can be served in multiple styles, such as a la plancha, asado, or impanizado (breaded). Saturdays are the only days that the carnicerias sell beef, and on this day vendors sell tacos or sandwiches with carne asada, or one will prepare a dish with picadillo (ground beef). Sundays are the days for rest, but it is customary to eat mondongo, which is cow intestine prepared overnight. I have both observed and been told that the people of Pisté are accustomed to, and very content with, this cycle.

When I made my identity as vegetarian clear, the first thing my homestay mother insisted was that “the meat here is natural, not frozen, but fresh.” Based on my observations, much of this is true. Many people in the town prefer to purchase chicken that has just been killed that morning, and certain meats are only available on the specific traditional days, as mentioned previously. This serves as a basis for both justifying and prioritizing meat consumption.

While the people of Pisté are steadfastly accustomed to these five staples, there are many not-so-regional foods that have been combined with the regional staples, and these have become a very traditional part of the diet. These foods are inconsistent with those regional trends mentioned previously yet they often feature some regional characteristics. For example, “Sobritas,” a Frito Lay label, are sold in every convenient store, including pharmacies—a contradictory feature of only privately owned pharmacies[9]— and out of homes. The term is used to define all potato-chip related snacks, and it is common to see young kids walking the street with a bag of Sobritas drizzled in a chile sauce that the stores provide complimentarily. These convenient stores also sell foot-long loaves of French bread that are popularly used for tortas, or sandwiches, with whichever meats are available in the kitchen that day. These “barras” frequently replace tortilla with multiple dishes, and as they are purchased by the half dozens it is not uncommon for a person to eat more than one with a meal. Mayonnaise is used primarily for tortas but is also used for eggs, tuna and spread on elotes. Sweet additions such as sweetened condensed milk and multiple syrups are used for drinks from frappes to machacados, a drink with mashed banana and multiple flavoured syrups. Flour tortillas were employed in the kitchen at La Gran Chaya for quesadillas, empanadas and other popular Mexican meals; corn tortillas are almost never folded and fried with meats or cheeses inside, as flour tortillas would be. Hot dogs and hamburgers are sold every night in the town center, save Saturdays, and Doña Diana said that her restaurant receives little attention at this time.

Most importantly, Coca Cola is the coffee, the water, and sometimes the medicine of a great percentage of the people in Pisté. Some say that it’s medicinal, and is consumed to cure headaches and even relax a person with high blood pressure. Doña Victoria and Don Viviano said that when they were young, they did not drink nearly as much Coca Cola as is consumed today, and Doña Luisa said it wasn’t consumed whatsoever when she was a child. Today, the majority of people will say that they need their Coca throughout the day, even those who say they religiously exercise. Coca Cola and other refreshments are served at parties, frequently in lieu of water.

Baklanoff’s comparison between life in the Yucatán city of Cancún and Tinum, a rural town, sheds light on the reason why these non-regional foods have been adopted and are now preferred. He observed that if a large number of young men in Tinum abandoned the milpa to seek work in the cities, over time the village would no longer be self-sufficient in food production. He went on to say that, “if the village could no longer produce its own food, there would be long-term implications for diet, gender roles, family structure, as well as the loss of traditional ties to the land (2008:126).” According to the information I received from my informants, the few men that have continued to work in the fields near Pisté face many troubles due to lack of rain and poor climactic conditions; my informants said that the “tierra es muy dura” in this region of Yucatán while in other regions of México the land is more fertile. As a result, the respective diets are quite different. Due to these conditions, as well as the globalization of which Baklanoff speaks, vegetables in Pisté are more expensive in other parts of México, and for this reason it is difficult to break the habit of omitting these more nutritious foods from the diet, according to multiple informants. At the same time, informants said, “the people here are not accustomed” to including these foods, which is another idea that further perpetuates the consumption habits of the Yucatecans in Pisté. Likewise, the need for sabor that I previously mentioned explains the popular use of many additions, especially flavored syrups and mayonnaise.

When it comes to traditional dishes[10], there are certain rules embedded in their preparation, which I was able to observe during my participant-observation at La Gran Chaya. Tacos, salbutes and panuchos with pork will only contain onion, and will never contain lettuce, tomato or avocado. Handmade tortillas must be a perfect thickness, diameter and shape. Rice and beans are only paired with fuller meals such as melanesa or brazo de reina, and the form in which beans are eaten depends on the dish; colado, or blended beans are eaten with egg while whole beans are paired with rice, meats and soups. Contrarily, neither the cooks nor the customers seemed to care if a hair topped one of their tacos.

NOTIONS and PRACTICES OF HEALTH

I would like to comment on the specific language used while discussing food. The term “cholesterol” is not used in terms of levels of cholesterol; if one has high cholesterol, they simply have colesterol; it is the same case with high blood pressure, which is referred to as presión. Poor diets are described as such almost solely in terms of two evils: grasa and azucar. Terms such as carbohydrates and sodium are not used in description unless I had introduced them to the conversation. The word gastar, meaning “to waste” is used to refer to food as a resource that runs out, as well as being used in the etymological sense of the word, which is “to devastate, ravage, [spoil or] ruin.” This came into play in a couple interesting ways. For example, if a bottle of refresco, specifically Coca Cola, is not consumed in an efficient manner, it is perceived as being “wasted;” this may be due to the carbonation quickly expiring, or the idea that everyone at the table is understood to have a beverage with their meal, and this beverage is almost always a soda such as Coca Cola.

To the common person in Pisté, making time for the three main meals is almost always a priority. I spoke with a taxi driver named William Briceño about the importance of food, and he says that despite his busy schedule, he tries to eat “normally.” For this reason, he will always go home to eat lunch, which is the largest and the most anticipated meal of the day. After eating a small breakfast of biscuits or bread with coffee, Briceño will go to work. If he is hungry on the road, he, like other taxi drivers, will stop for a small empanada or piece of fruit from one of the loncherias along his route, primarily to hold him over until he can make it home to eat a full lunch with his family. In the spirit of tradition, he will dine on a small dinner in the evening, possibly a small sandwich or another meal of coffee with biscuits.

According to Briceño and multiple other informants, the ideal routine of the “tres comidas” is practiced to maintain healthy digestion throughout the day, finishing the day with a light meal so that one does not sleep on a full stomach. There are variations of this diet, for example, my informants who partake in exercise or are dieting say they prefer to eat five small meals a day, which helps them eat less. Likewise, I observed that many people in Pisté are sure to include plenty of limes, garlic and chile in their diets to keep their immune system kicking and their bowels clear.

However, these somewhat uniform perceptions of health are very frequently contradicted by lifestyle. In many cases, for the sake of keeping it simple, the family will order a pizza or buy meat, cheese and French bread for late night or early morning sandwiches, of which are usually eaten in the plural. The average family in Pisté will attend a fiesta at least once a week, where there is an abundance of soft drinks, tortilla and savory meat dishes from cochinita to chicharra, carne asada to queso relleno. These parties traditionally occur late in the evening and continue into the early morning hours, sending families directly to bed with stomachs full of meat and soda. On some weekends or holidays, families will go to multiple parties in succession, eating full meals at each one. In this way, health as the people understand it is challenged by the social importance of food, a concept on which I will expand later in this report.

As mentioned, sicknesses of concern include digestion problems, therefore eating regularly is important. At the same time, there are rules governing what can and cannot be consumed together. Dairy and citrus, or as well as dairy and chile, should not be consumed during the same meal, as they can result in stomach problems such as indigestion and diarrhea; banana in any combination with beer will cause similar intestinal illness. Seafood and beef in combination could cause rashes, and seafood can cause a number of ailments if consumed too late in the day. Likewise, citrus will increase cramp pains for women on their menstrual cycle, and therefore women shouldn’t eat lime with their meals during that time. Surprisingly, none of my informants told me of any dietary changes recommended for pregnant women, save that women should stop eating tortilla during the last trimester because the child is nearly fully developed and does not need excessively heavy tortilla to continue growing.

Conversations about food with a great majority of informants from Don Viviano’s generation as well as young adults almost always gravitated towards concerns about long-term health. Don Viviano attributes emphasis on meat consumption and excess of Coca Cola to chronic illnesses such as high cholesterol and diabetes. Many of my family members blame their own panza, or belly, on their love for pork and tortilla. The majority of my informants, including doctor Jose Enrique Reyes Colli as well as Don Briceño, blame obesity and chronic illness on the relaxed, sedentary lifestyle that the majority of residents in Pisté practice, and nutritionist Lizbeth Arellano said that the highly structured weekly Yucatecan diet perpetuates practices that do not allow change. Furthermore, a local physical education teacher who sells some of the only fruit salads in the town[11] said that the parents perpetuate the poor, unbalanced diets of their kids outside of school, so issues such as diabetes and obesity have ailed younger age groups.

The Centro de Salud, the government run-clinic in Pisté, has health information pamphlets, dietary information sheets and charts on the walls of both the waiting rooms and examination rooms. One wall features a calendar that, for every month, offers recipes and recommendations for healthy meals based on the foods available in a certain state. Yucatán’s menu is placed over the month of December, and it features a number of fried foods that use forms of masa de maiz, potato and egg; the menu features less green but does employ mango, banana and Chaya, a regional leafy green with a great amount of nutritive value used popularly in many dishes as well as blended drinks (Ross-Ibarra, Molina-Cruz 2002). Because the calendar seems to manifest the idea that low-income families have trouble purchasing fruits and vegetables to supplement their meals, the calendar also provides a chart showing the seasonality of many vegetables and fruits so that families can plan to purchase them when they are cheaper.

However, the idea that low-income families is less likely to eat fruits and vegetables than high-income families is a fallacy. Many of my sources gave me mixed answers on this topic, but one consistent answer was that upper classes eat more meat, while lower classes emphasize beans, rice and vegetables high in protein; however, as Doña Diana Burgos, the owner of La Gran Chaya, said, “…but everyone eats Sobritas!” Regardless, I have not come across any families nor dishes that place vegetables at the center; vegetables will often come as a salsa or alone as avocado. Conversations with a few of my younger informants revealed that people simply don’t enjoy eating vegetables, and vegetables must be prepared in a very flavorful manner to be a part of their diet, that is, part of a caldo de pollo or as tomato and avocado to accent a meat dish. According to information from both the nutritionist and my observation, it is rare to use vegetables as a replacement for meat. If meat is scarce, it will likely be replaced with egg or, in its scarcity, made into a caldo (soup) with a flavorful recado. Likewise, the richness of the recado varies between classes, as recado blanco contains less herbs and spices and is used by lower classes, and recado negro has more flavor, is often spicier, and is used in dishes by those with higher economic status.

Nevertheless, it is customary among all social classes to consume a great amount of meat, and as my informants say, grasa. As Don Viviano said, the idea of social class had so affected the Maya people after the introduction and sale of meat became a regular part of the lifestyle in Yucatán that the poor tried to add more meat to their diets just to bridge the gap between the well-off and the humble.

Today’s diet is stubbornly set on the seven-day schedule, and for this reason, many of my informants insisted that it is difficult, even impossible, to make dietary changes, even if they desire to do so. Similarly, from the data I collected, it is very uncommon for women to try new recipes or other regional foods, especially because the resources are unavailable for said kitchen experimentation. That being said, chronic illnesses and health as perceived by the people has encouraged the popularity of diet and exercise programs in Pisté: Zumba fitness and Herbalife.

HERBALIFE: A MINIATURE CASE STUDY

Herbalife[13], a dietary supplement program that offers an array of nutritious beverages that serve to replace, or supplement diet and “improve well being” came to Pisté about one and a half years ago, and since its introduction has procured between 40 and 50 members, and those to whom I spoke have been a part of the program for durations ranging six months to six years. The Herbalife plan suggests that clients consume the three-beverage supplement for both breakfast and dinner, eating their customary lunch in between. Each “meal” costs a client $37 pesos, a price that employee Margarita insists is a practical cost of replacing the coca cola in the daily diet.

Herbalife serves as both a clinic and a social gathering, where clients can either visit quickly before work or stay and converse with others at a table under a television. Based on my observation and employees’ testimonies, people from all social classes and walks of life are a part of the Herbalife clientele in Pisté, and according to some of the clients with whom I spoke, their well being has improved significantly since consuming the product. Some said that they have lost weight namely from replacing meals with the product, while others said the product cured their depression and headaches. Some clients even said that they couldn’t imagine having a good day without consuming the product at least once.

Incentive for joining the program comes predominantly from the fact that the clients realize that they cannot change their diets significantly enough to make a change in their health. Multiple clients agreed that agriculture in Pisté is not what it should be and had been; they said that the land in this region is less fertile than in other parts of México, and for that reason agriculture is at a lull. As a result, produce is too expensive to be a practical addition to the diet. One woman is quoted as saying, “in other parts of Mexico they can have a bowl of fruit on the table, but not here, because it will just go bad … it is not part of our custom to eat that way.”

Overall, both employees and clients say that they consume the product not only to improve their own health, but also avoid the chemicals that are found in all food on the market today in produce and meat alike. It is interesting to note that when I asked the employee whether there were chemicals in the product, she said yes, “but only in amounts sufficient to clean the body.” The fact that food un-laden with chemicals is hard to come by is not merely discussed behind the curtain at the health club. An acquaintance of mine, Don William, lamented about the calcium, phosphorous, vitamin C and other additives in the refined corn flour, MASECA, because he feels that it is wrong to eat foods with unnatural additives.

Through my observations of the space and discussions with clients of Herbalife, I was able to glean information about individual ideals of well being, or bien estar. While some clients expected to lose weight and did not, they said that their bodies felt better nonetheless and for that, they appreciate and swear by the product.

THE SOCIAL SIGNIFICANCE OF FOOD

The plain truth is that life in Pisté revolves around food. The women wake early to prepare food either for consumption later in the day or for sale. By 10 a.m., people have already eaten breakfast and are out buying food for the traditionally late lunch. The tortillerias are always busy; each family will send someone at least twice a day to pick up hot, fresh tortilla. While dinners at home are typically small and insignificant, families or couples will go to the town center to enjoy an ice cream, hot dog, hamburger or frappe. If people choose to stay home, it is often to watch telenovelas while preparing food for the next day.

At the dinner table, meat is treated as a commodity while fruits and vegetables are treated as if they are an infinite, disposable resource. I imperfectly sliced a china from the tree in our backyard, and instead of trying to salvage the remainder of the fruit, Indalecia threw mine away and fetched another. Limes are cut liberally for the table, and if one or two sliced limes are not used, it is of no concern. Partially cut avocadoes, tomatoes and onions, if not used, are left sitting on tables, shelves, and in bowls; they are seldom refrigerated or covered. Fruits are shared and consumed as if they are sweets; people suck on huaya fruits while watching television, mangos are both sold and eaten like popcorn and melons are enjoyed in moderation or made into juices with an abundance of sugar.

I found many correlations between the idea of simple food being humble, while spicy and flavorful food was richer; at the same time, meat was always associated with upper class. Likewise, there are many cultural expressions surrounding the idea that simplicity comes in the form of vegetables or a simple legume. For one, the phrase “we were only given tomatoes to eat” is used to communicate that the giver of food was miserly and the food given was limited. Based upon what I found in my analyses, I believe it is safe to say that many of the homes in Pisté will not be serving tomatoes. Regardless of the economic situation of the household, the food will continue to be served until one is fully satisfied.

The culture of eating as the Yucatecans do— plenty of meat, chile, and food in general— is preserved and perpetuated by the symbol of food as a mechanism for bonding. The women of the household share time together in the kitchens, talking or watching telenovelas while they prepare food. The older women teach the younger girls as young as age ten to perform tasks in the kitchen from making tortillas to breading meat for frying. Don William, the taxista, said that among other reasons, it is important for him to return home for the three main meals, as he enjoys spending that time with his family. Don Viviano insisted that the family stop selling tacos on Sunday mornings so that they can spend time with one and other, and similarly other families are likely to stay in their homes on Sunday as they don’t need to stop at a taco stand while on their way to work.

Likewise, the consumption of foods such as meat and chile are perpetuated by an aggressive “machismo” sort of energy, in which men at the table will chide one another if meat is missing from a plate, and chile is consumed primarily among men, the hottest ones being a test of sorts to prove who can consume the hottest without cooling off with a beverage. Likewise, family members are likely to chide their loved ones about diet and appearance alike, in the spirit of the Mexican humor of which my host family shared with me liberally.

RESULTS OF THE RESEARCH PROJECT and ANALYSIS

To answer my research questions, I found that food is always perceived as creating health, but the amount and type of health created is not necessarily measured in terms of nutritive value. I found that to the people in Pisté, food creates social health, and is healthy in that it fills the stomach and conquers hunger. This view can be connected to the traditional staples passed down from 7 thousand years ago; the people realize that corn is mere carbohydrates, beans today are protein often corrupted by pork fat, calabaza is in many ways an empty vegetable, and chile is flavor. However, in combination, these foods provided the fuel for civilization, and for Don Viviano, these foods provide the fuel for existence. While these staples have been manipulated in many ways, they still exist in the Yucatecan diet and now serve a different purpose.

Due to the wide range of data collected over a short period of four weeks, there is not much analysis to offer unless more in-depth fieldwork were to be conducted for an extended period of time. However, as mentioned in the introduction of this paper, I recognized that pride was at the axis of the self-perpetuating cycle of food consumption. Simply asking questions about food didn’t really get me far into ideas about well being, but I did realize that cultural pride and love for social interaction, especially at the dinner table, is one of the most important aspects about food. Whether it is maintaining the four traditional staples in the majority of complete Yucatecan dishes, or consuming excessive amounts of meat, cooks as well as consumers of food are proud of their food culture. In Pisté, food has the power to bring people together, to share individual flavors and stories, and to maintain cultural heritage.

I found that for the most part, the people choose to be ignorant to the consequences of their food choices, or decide that they are helpless based on the resources to which they have access. However, the most compelling aspect of the food culture that has perpetuated the diet is the social climate that can be explained by the theories of both rites of passage and law of reciprocity. As mentioned previously, young people will be pressured into eating both certain types and certain amounts of foods to fit in with the social group. The food at parties is nonnegotiable, and families very frequently share from common plates and bowls during meals. The laws of both balanced and general reciprocity apply to the large shared household of the family in Pisté; family members will bring home a bag of bread or prepare a meal while rarely expecting reparation. Because of the social implications connected to food, it is difficult to break from the traditional diet, as such a break would result in a break from the social network.

Through analysis of the population chart[14], I found that the majority of the population lies between age groups 10-24, consistently in men and women. Through speaking with representatives from these age groups I found that attitudes towards food and diet were quite scattered; a great number were preoccupied with playing soccer daily, some with going to the gym, and a significant number attended Zumba classes regularly. However, at the other end of the spectrum lie the subjects, such as my homestay brothers, who rose late in the day and filled their day with video games and television, eating in excess. According to information from the physical education instructor, these younger groups are receiving dietary advice, or a lack thereof, from their parents, of an age group with a significantly lower population. Although I lack statistical data on causes of mortality, I did speak to a number of informants that has, and know someone that has, a chronic illness such as diabetes, high cholesterol or triglycerides. I came to understand this relationship as another example of the perpetuation of consumption habits; the fate of the youth is in the hands of the age groups that have been diminishing by means of their own consumption.